Trio FORMIDABLE – COMME DES ROSES

Les Chansons d’ Aznavour.Â

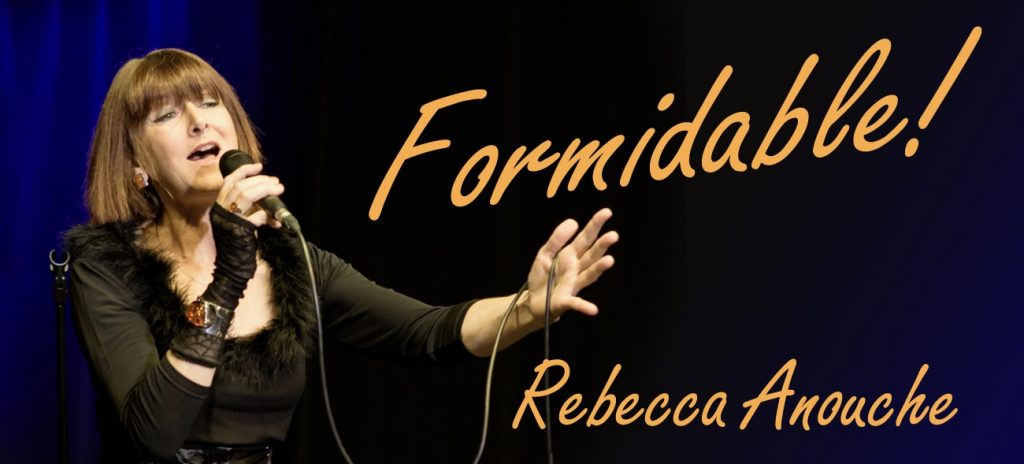

Rebecca Anouche (F) – voice

Ivanila Lultcheva (BUL) – cello

Manu Mazé (F) – accordion, piano, arrangements

Charles Aznavour (* 22. Mai 1924 in Paris; †1. Oktober 2018 in Mouriès), one of France’s most celebrated singers of popular songs as well as a composer, film star and lifelong champion of the Armenian people, has died at his home in Mouriès, in southwestern France. He was 94.

His death was announced on Monday by the French Culture Ministry. Local authorities said he died overnight.

At an age when most performers have long retired from the footlights and the brutal, peripatetic life of an international star, Mr. Aznavour continued to range the world, singing his songs of love found and love lost to capacity audiences who knew most of his repertoire by heart. In his 60s, even then a veteran of a half century in music, he laughed off talk of retirement.

“We live long, we Armenians,” he said. “I’m going to reach 100, and I’ll be working until I’m 90.”

His accomplishments were prodigious. He wrote, by his own estimate, more than 1,000 songs, for himself and others, and sang them in French, Armenian, English, German, Italian, Spanish and Yiddish. By some estimates, he sold close to 200 million records. He appeared in more than 60 films, beginning with bit parts as a child. His best-known film role was probably as a pianist with a mysterious past in François Truffaut’s eccentric 1960 crime drama, “Shoot the Piano Player” — a part that Truffaut said he had written specifically for Mr. Aznavour.

Charles Aznavour was born in Paris on May 22, 1924. (Most sources say his name at birth was Chahnour Varenagh Azavourian, but some give his original given name as Charles and his original surname as Aznaourian.) His parents, Mischa and Knar, had come to France fleeing Turkish oppression. When they were denied visas to America, they opened a restaurant near the Sorbonne and made the city their home.

Charles’s parents instilled a love of music and theater in him and in 1933, when he was 9, enrolled him in acting school. He was soon part of a troupe of touring child actors. At 11, in Paris, he played the youthful Henry IV in a play starring the celebrated French actress and singer Yvonne Printemps.

But his earliest inspirations were singers, notably the French stars Charles Trenet, Édith Piaf and Maurice Chevalier. “Trenet for his writing, Piaf for her pathos and Chevalier for his professionalism,” he told The New York Times in 1992, “and all three for their tremendous presence on stage.”

Also high in his pantheon were Carlos Gardel, the Argentine tango singer, and Al Jolson. “Gardel and Jolson were far apart,” he said, “but they had the same pathos.” He learned his idiomatic English from Frank Sinatra’s records, but he considered Mel Tormé and Fred Astaire his favorite American singers.

Mr. Aznavour’s career spanned the history of the chanson realiste, the unvarnished tales of unrequited love, loneliness and anomie that found their apotheosis in the anguished voice of Piaf. He wrote songs for her and for Gilbert Bécaud, Léo Ferré, Yves Montand and others. When Piaf rejected one of his songs, “I Hate Sundays,” he gave it to Juliette Gréco, then the darling of the Left Bank philosophers and their acolytes. When Piaf changed her mind, she was enraged to find that she’d lost the song and, according to François Lévy, one of her biographers, confronted Mr. Aznavour, shouting, “What, you gave it to that existentialist?”

He spent nearly eight years in Piaf’s entourage, as a songwriter and secretary but, he insisted, not a lover. (“I never had a love affair with her,” he said in 2015. “That’s what saved us.”) He accompanied her to New York in 1948 and stayed for a year. “I lived on West 44th Street, ate in Hector’s Cafeteria and plugged my songs,” he recalled, “with no success.”

Back in Europe, he spent years singing in working-class cafes in France and Belgium, without much success. One critic wrote dismissively of his “odd looks and unappealing voice.”

Then, in 1956, he was an unexpected hit on a tour that took him to Lisbon and North Africa. The director of the Moulin Rouge in Paris heard him at a casino in Marrakesh and immediately signed him. When he was back in Paris, offers poured in.

In “Yesterday When I Was Young,” an autobiography published in 1979 — it shares its title with the English-language version of one of his best-known compositions — Mr. Aznavour recalled a Brussels promoter who had ignored him for years and was now offering him a contract. He offered 4,000 francs. Mr. Aznavour asked for 8,000. The promoter refused.

The next year, he offered 16,000.

“Not enough,” replied Mr. Aznavour, now a major star. “I want more than you pay Piaf.” Piaf was then making 30,000 francs. Again the promoter refused. The next year, he gave in. “How much more than Piaf do you want?” he asked.

“One franc,” Mr. Aznavour said. “After that I was able to tell my friends I was better paid than Piaf.”

In 1958, the French government lifted a longstanding ban on allowing some of Mr. Aznavour’s more explicit songs — like “Après l’Amour,” which recounts the aftermath of an episode of lovemaking — on the radio. “I was the first to write about social issues like homosexuality,” Mr. Aznavour told The Times in 2006, referring to his 1972 song “What Makes a Man?” “I find real subjects and translate them into song.”

He returned to New York in 1963 and rented Carnegie Hall, where he performed to a packed house. (Among those in the audience was Bob Dylan, who later said it was one of the greatest live performances he had ever witnessed.) A triumphant world tour followed.

Thereafter, the United States became a second home. Mr. Aznavour performed all over the country, often with Liza Minnelli. He became a fixture in Las Vegas for a time and there married Ulla Thorsell, a former model, in 1967. She was his third wife.

Mr. Aznavour had six children. Complete information on survivors was not immediately available.

As a child, Mr. Aznavour watched his father go broke feeding penniless Armenian refugees in his restaurant. As his fame grew, he became a spokesman and fund-raiser for the Armenian cause. He organized help worldwide after an earthquake killed 45,000 people in Armenia in 1988. And when the country broke away from the crumbling Soviet Union in 1991, it made him an unofficial ambassador. He displayed the Corps Diplomatique plaque on his car as proudly as he wore the French Legion of Honor ribbon in his lapel.

President Emmanuel Macron of France said in a statement on Monday: “Profoundly French, viscerally attached to his Armenian roots, famous in the entire world, Charles Aznavour accompanied the joys and sorrows of three generations. His masterpieces, his timbre, his unique influence will long survive him.”

In 2006, at the age of 82, le Petit Charles, as the French called him (he was 5 feet 3 inches tall), began what some — although not Mr. Aznavour himself — called his farewell tour. After several months in Cuba that year, recording an album of his songs with the pianist Chucho Valdés, he moved on to a 10-city swing through the United States and Canada, beginning at Radio City Music Hall. It was just the English-language part of the tour, he said, with England, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa to follow.

He continued performing almost to the end. He had broken his arm in May, but at his death he had concert dates booked in France and Switzerland for November and December.

Reviewing a 2009 concert at New York City Center, Stephen Holden of The Times wrote that Mr. Aznavour “displayed the stamina and agility of a man 30 years younger.” A 2014 performance at the Theater at Madison Square Garden was billed as his final New York appearance, but he suggested in an email interview with The Times that he might change his mind.

He continued writing songs as well. “My Paris,” a musical based on the life of Toulouse-Lautrec for which he wrote the score, was staged at the Long Wharf Theater in New Haven in 2016.

In recent years, health problems inevitably slowed him down, but he showed no sign of stopping. “We are in no hurry,” he said in 2006. “We are still young. There are some people who grow old and others who just add years. I have added years, but I am not yet old.”

Frank J. Prial, a reporter for The New York Times, died in 2012. Peter Keepnews and Aurelien Breeden contributed reporting.

A version of this article appears in print on Oct. 2, 2018, Section A, Page 22 of the New York edition with the headline: Charles Aznavour, Crooner Who Packed Houses the World Over, Dies at 94.

You are my love, very, very, véri, véritable

Et je voudrais un jour enfin pouvoir te le dire

Te l’Ă©crire

Dans la langue de Shakespeare

Je suis malheureux

D’avoir si peu de mots Ă t’offrir en cadeau

Darling I love you, love you, darling, I want you

Et puis c’est Ă peu pres tout

You are the one for me, for me, formi, formidable

But how can you see me, see me, si mi, si minable

Je ferais mieux d’aller choisir mon vocabulaire

Pour te plaire

Dans la langue de Molière

Tu n’as pas compris

Tant pis, ne t’en fais pas et

Viens-t’en dans mes bras

Darling I love you, love you, darling, I want you

Et puis le reste, on s’en fout

You are the one for me, formi, formidable

Toi qui te moque de moi et de tout

Avec ton air canaille, canaille, canaille

How can I love you?