Brigitte Franzen:

“paradise lost” as heterotopia

In “Other rooms / other spaces”, his much-quoted lecture, Michel Foucault defines the garden as hĂ©tĂ©rotopie – a term which designates “real places” understood to be the actual realisation of utopias. Heterotopias are said to be able “to unite several spaces, several entities that are in themselves disparate and incompatible, in one single place: in such as way that conditions marked or reflected by those entities, are neutralised or inverted.” Apart from psychatric clinics, cementries, theatres, cinemas, museums and libraries, brothels, colonies and ships, which all present their various different heterotopic characteristics, it is the garden that Foucalt considers “perhabs to be … the oldestof these heterotopias with their conflicting placements.” He describes the Persian garden as a sanctified space, whose division into four parts represents the four corners of the world, and whose holy central space is the navel of the world.

Foucalut describes how such a garden was reproduced and “mobilized”, in Persian carpets. In his view, this transformation shows that the garden is both “the smallest plot of land”, and “the world in its tatality”. He therefore calls the garden a “sanctified and all-embracingheterotopia”.

Bagh-e Eram, Schiras

Japanese Gardens at the Chicago Botanic Garden (Elizabeth Hubert Malott)

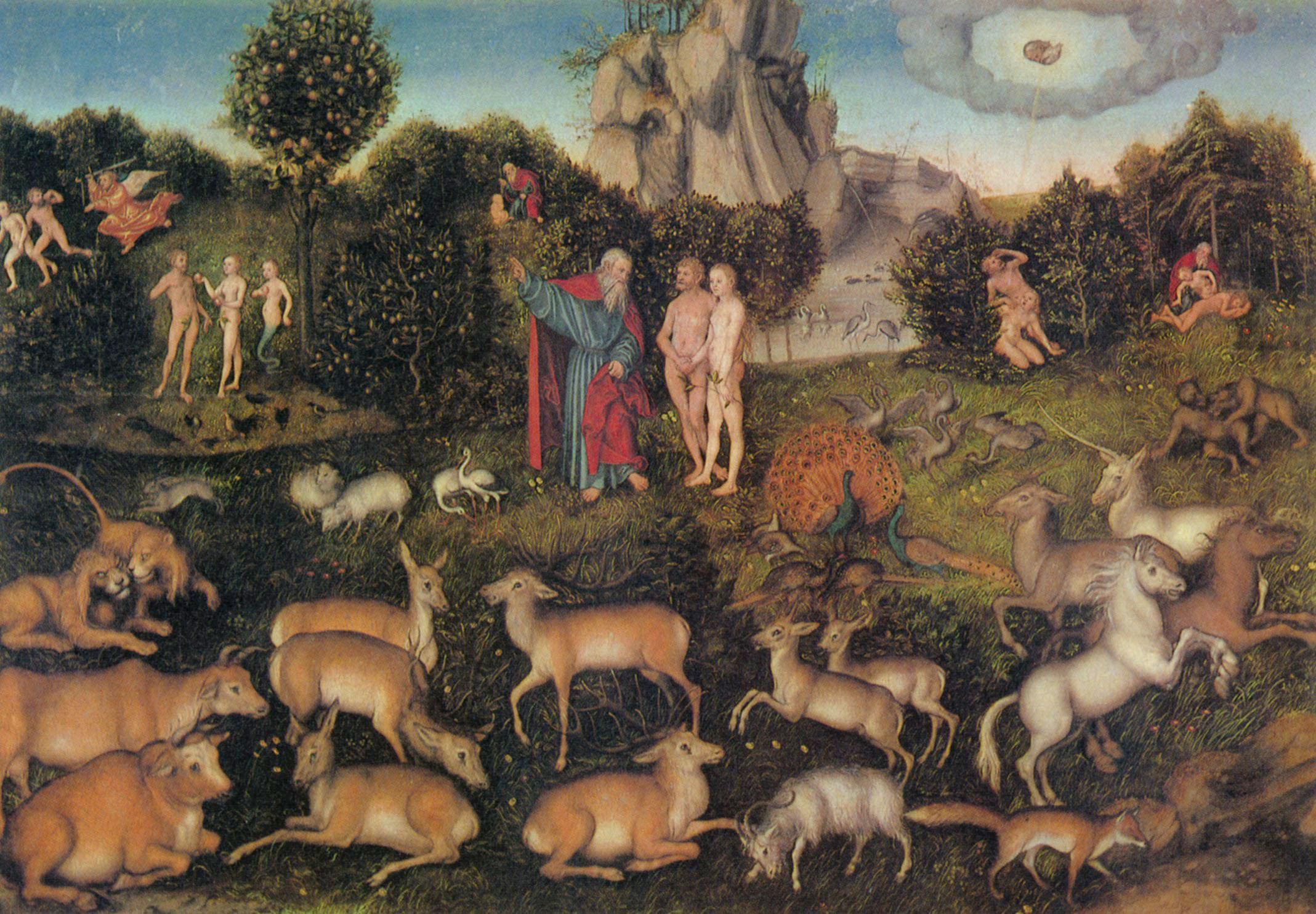

In this definition, Foucault´s takes his bearings from an image of the garden that is close to the Islamic (and also the Christian and Jewish) principle of the origin of paradiese, or the Garden of Eden. There, becming truly human is inexorably linked with man´s place to live as assigned to him by God, that is, in the paradise-like garden. As long as there is no Fall, man has no place outside this place. At the same time, paradise unites in ttself all possible other places: there isn´t any question of “the outside”, even … (…)

Das Labyrinth im Parc del Laberint d’Horta in Barcelona, Katalonien (Spanien), Foto Till F. Teenck

Heian-jingu shinen (Heian Shrine garden), Kyoto, Japan

Not before the tasting of the forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge will human perception be altered, indeed distorted: human beings realise they are naked; they realise and painfully experience the border that separates paradise from “outside”, from the second type of nature that is land to be worked. In this way, the need for survival is explained, in cultivating this land, and in striving (at least) for something similar to paradise – which will at all events be unreachable.

The garden is a place of longing, a place in the mind, where the wish to return is impossible to fulfill. In this context, gardens are places in between; places that simulate the conditions of paradise, that have been fought for an won from nature: which however must never show the labour invested in them. To put the “creator” in first place, the parctical gardener often remains invisible, in artistic ways of redeption as well as in art history´s reception of the garden.

In: Brigite Franzen: Die vierte Natur. Gärten in der zeitgenössischen Kunst. Köln: König 2000.

Etymologien

Botanischer Garten Graz, Altes Gewächshaus ,1870 Garden, presumably from the Gotic gards, garda >twigs Lukas Cranach d. Ă„. Das Paradies, 1530 Paradise, from the Hebrew pardes, Old Persian pairidaehebrza >walling-in<, Old Greek paradeisos >fencing, garden, a green place< (…)

Garden

(Picture credit:copyright Martha Schwartz)

Paradies

Xenophon (434-355 BC) used the word “paradeisos” to designate the royal gardens of PEria. In general usage, paradise is the New Testament equivalent of the Garden of Eden, the >primal icon< of the most beautiful of all gardens, where lived the first human couple until the Fall. In the Apocalypse, paradise is the hereafter, the place of the departed, the blessed. (…)

In the pictorial arts: a garden landscape with an abundance of water (the four rivers of paradise) and of sustenance (the Tree of Life). (…)Sources:

Uerscheln, Kalusok: Wörterbuch der europäischen Gartenkunst,Reclam 2001/2003

Wilhelm Gemoll: Griechisch Deutsches Schul- und Handwörterbuch, Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky, 1936.